Small caps poised to benefit

as Fed pivots to easing cycle

November 2024

After months of speculation about the size and timing of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s transition to a new easing cycle, the Fed made it official after its September 18 meeting with the first cut to the benchmark lending rate since the height of the Covid-19 pandemic. With inflation now appearing more under control, the next question for the Fed is whether it can successfully engineer a so-called soft landing for the economy, bringing short-term rates down further in the process. If the equity markets are any indication, there seems to be a good deal of confidence that the Fed can succeed. For investors taking a second look at their stock allocations as this transition unfolds, we believe that small caps look particularly well positioned as interest rates continue to fall.

Small-cap stocks have outperformed during past easing cycles

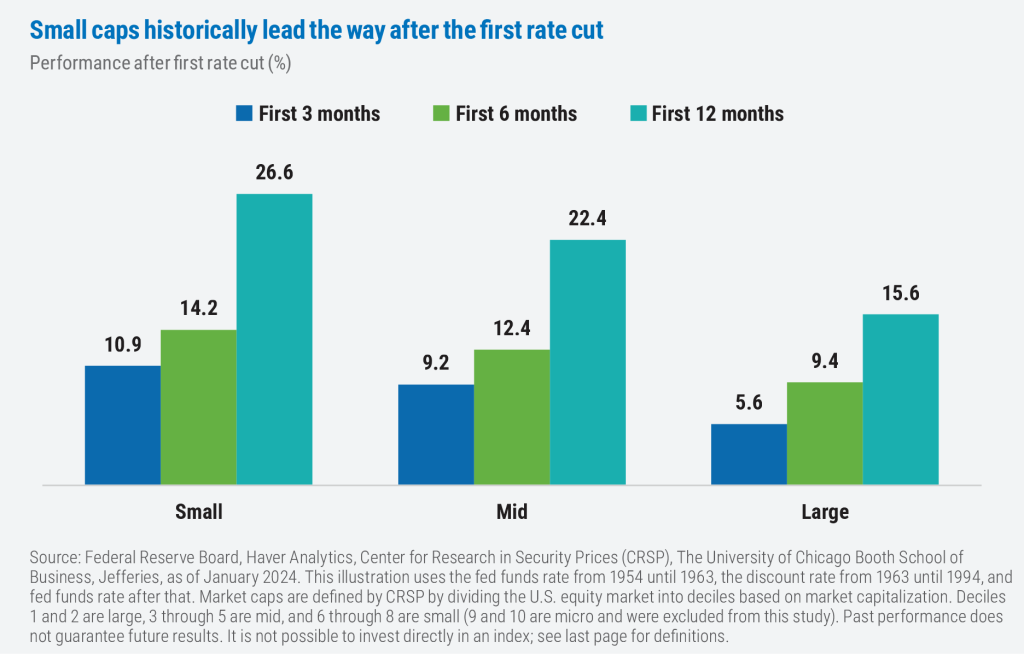

Rate cuts generally have been good news for equities across market capitalizations—which in some ways highlights how unusual the circumstances surrounding September’s initial rate cut were. (The Fed cut rates an additional 25 basis points in early November, as expected.) More often than not, the Fed is cutting rates in response to deteriorating economic conditions rather than recalibrating after trying to tamp down inflation or trying to preempt a cooling economy, as seemed to be the case this time. This explains why equities, on average, have been higher just three months after an initial rate cut: The worst economic news has usually already been priced into markets by the time the Fed begins cutting.

While three months has generally been sufficient time to see a bounce in stock prices, six and twelve months after an initial rate cut equities historically have fared even better. It’s worth noting how dominant small caps have been over all three time periods, leading the pack in each and outperforming large caps by more than 1000 bps over the one-year time horizon.

Lower borrowing costs disproportionately benefit smaller firms

It’s something of a given that smaller firms tend to employ greater leverage than larger firms, which also implies that they’re more directly affected by interest costs. Smaller firms also have naturally higher borrowing costs relative to larger ones given their debt is often rated lower, resulting in higher required interest payments.

For example, one series of Apple bonds with 30-year maturities (due in 2047) were issued with 4.25% coupons—for context, that’s a rate below the current yield on 30-year U.S. Treasuries.1 Dish Network, meanwhile—one of the largest positions in many high-yield bond indexes—issued five-year debt due in 2027 with a coupon of 11.75%. Both are publicly traded companies, but Apple’s market cap is currently in the neighborhood of $3.5 trillion versus around $3 billion for Dish.

While this is just one such example, the point illustrated is that lower prevailing interest rates disproportionately benefit smaller firms, which must often deploy a greater percentage of their working capital toward interest repayments.

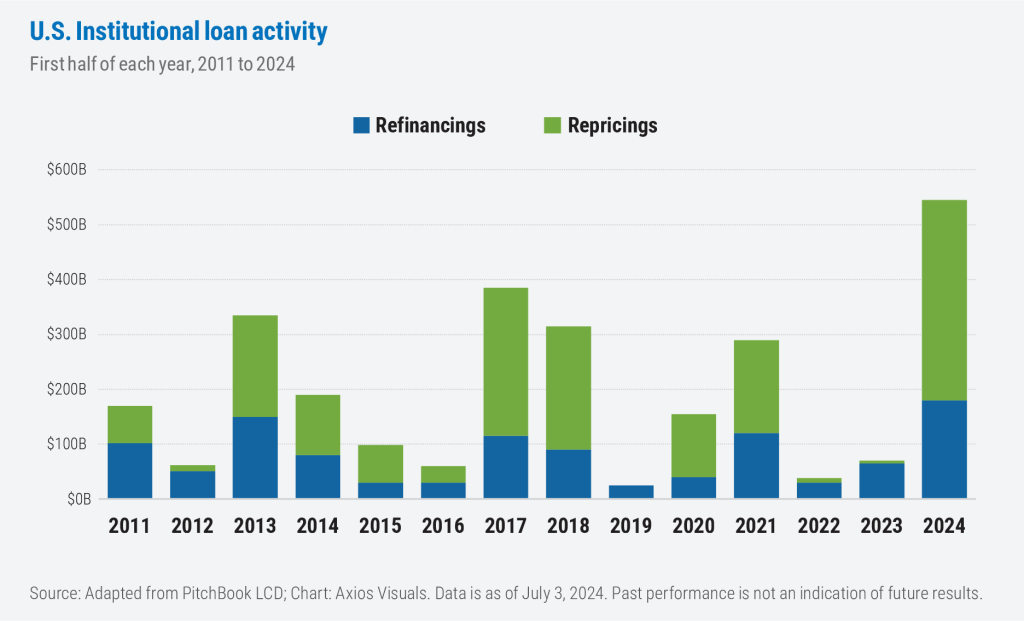

Even before the Fed’s recent rate cut, this year has seen an unusually high volume of refinancing of existing debt. To the extent that smaller companies have been able to participate in lowering their cost of capital, those savings directly impact their bottom lines.

Stock valuations and multiples tend to expand during easing cycles

With greater profitability, small cap valuations naturally tend to expand, which can kick off something of a virtuous cycle. Higher stock multiples (higher price/earnings or price/free cash flow multiples, for example) generally lead to higher market caps. Higher market caps, all else being equal, facilitate increased trading volume, more liquidity, and ultimately a narrowing of any built-in liquidity discount—i.e., higher prices. This cycle is, of course, predicated on a relatively stable economy, but even in the event of a recession, equity funds can often serve as a kind of backstop, setting a floor for small-cap multiples when investors dial down risk.

There are other tailwinds to valuations: Falling interest rates tend to have beneficial effects on many inputs that ultimately determine a company’s profitability—and therefore its share price—including financial statement line items like the cost of goods and services (COGS) and selling, general, and administrative (SG&A) expenses.

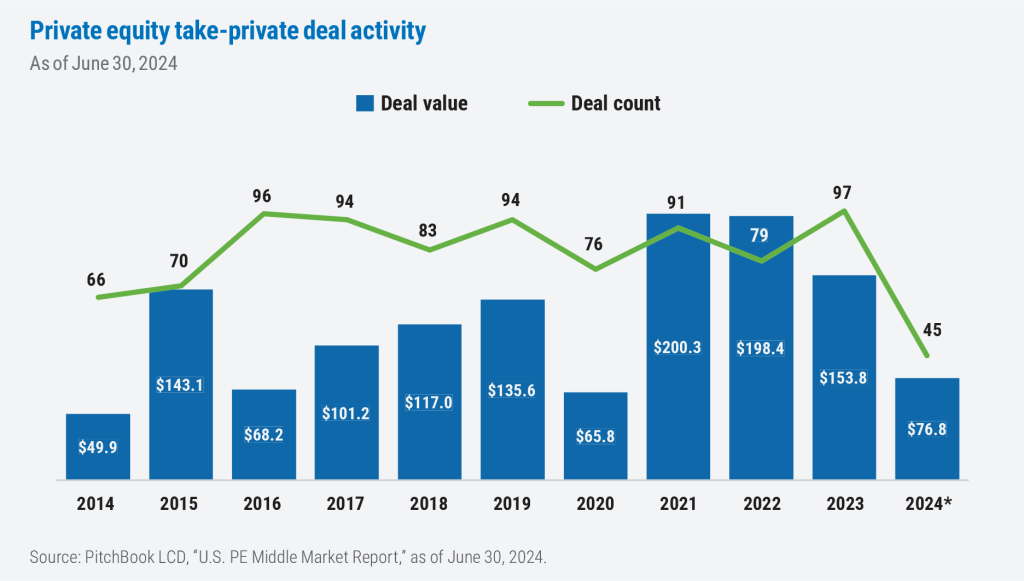

M&A activity typically accelerates as interest rates fall

Another byproduct of an easing cycle is greater merger and acquisition (M&A) activity. Higher stock multiples lead to deeper pockets for firms, meaning acquisitions can be achieved with either less dilution to book values and/or more accretion to earnings. Also, acquisitions lead to larger firms, which as discussed above, often leads to greater liquidity for the stock and higher valuations.

The benefit of higher M&A activity for small-cap investors is that shares of smaller companies are typically bought out at a premium, potentially delivering a profit for shareholders.

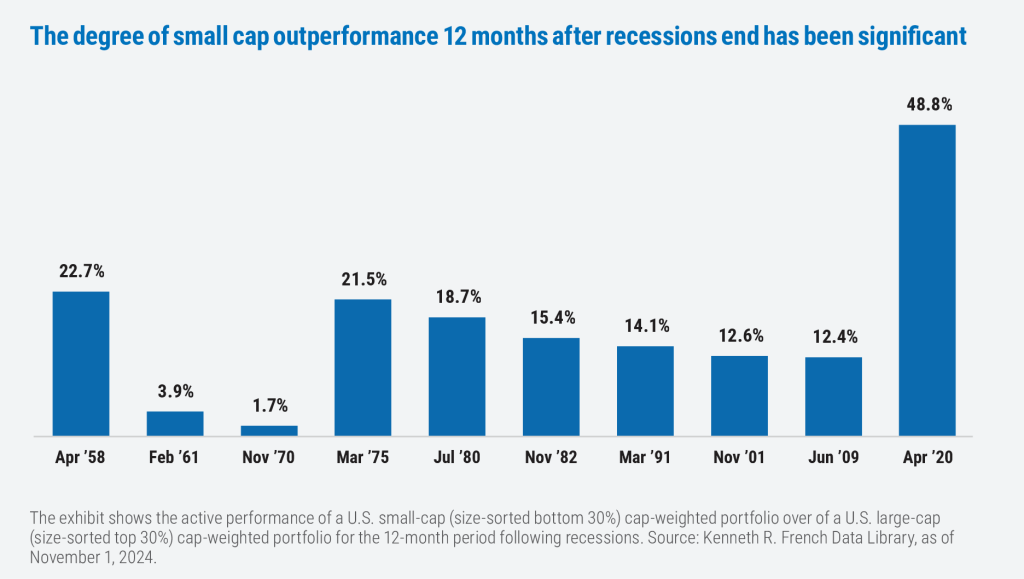

If all else fails, small caps have significantly outperformed large caps coming out of recessions as well

The chances that the Fed engineers a so-called soft landing are far from certain. Conventional wisdom suggests the size of the cut—50 basis points rather than a less aggressive 25—indicates the Fed has become focused on propping up the economy and helping to insulate it against a possible looming slowdown. With that in mind, it’s prudent to look at how small caps have performed around recessions. While studies from CRSP have shown that small caps tend to underperform large caps during the initial months of a recession (both segments of the market have historically recorded losses, unsurprisingly), they’ve significantly outperformed on the other side.2

In a rotation to small caps, not all investment options are created equal

In a final cautionary note, investors bullish on small caps should take care to know what they own. A recent study by Raymond James looked at nearly 300 actively managed small-cap mutual funds and 31 ETFs and found that in aggregate the funds had a sizable underweight to small-cap securities (defined as securities with market caps between $250 million and $3 billion). Strikingly, these funds on the whole had a nearly 14% overweight to large-cap stocks (defined as those with market caps greater than $11 billion); the Russell 2000 Index has approximately 2% of assets in securities of that size, mostly due to appreciation between scheduled index reconstitutions.3

All told, we see no shortage of tailwinds for small caps in the early phases of the Fed’s new easing cycle. The one key risk on the horizon is the possibility of a material economic slowdown or an outright recession. Time will tell whether the Fed ultimately achieves its soft landing—but if it does, we could see investor interest in small caps begin to really take off.

7337261.1

WPG Select Small Cap Value

A concentrated portfolio of our highest-conviction small-cap ideas managed by the veteran team at WPG Partners.

Small Cap Value

An established strategy targeting undervalued small companies in the United States.

1 United States Department of the Treasury, as of November 1, 2024.

2 Center for Research in Security Prices, as of November 1, 2024.

3 For reference, stocks with market capitalizations greater than $3 billion and less than $11 billion are generally considered mid caps.

The opinions expressed are those of the contributors as of the publication date and are subject to change. No forecasts are guaranteed. This commentary is provided for informational purposes only and is not an endorsement of any security, mutual fund, sector, or index. Boston Partners and affiliates, employees, and clients may hold or trade the securities mentioned in this commentary. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Index definitionsThe Russell 1000 Value Index tracks the performance of those large-cap U.S. equities in the Russell 1000 Index with value style characteristics. The Russell 2000 Index tracks the performance of 2,000 of the smallest companies traded in the United States. It is not possible to invest directly in an index.

Stocks and bonds can decline due to adverse issuer, market, regulatory, or economic developments; foreign investing, especially in emerging markets, has additional risks, such as currency and market volatility and political and social instability; value stocks may decline in price; growth stocks may be more susceptible to earnings disappointments; the securities of small companies are subject to higher volatility than those of larger, more established companies. This material is not intended to be, nor shall it be interpreted or construed as, a recommendation or providing advice, impartial or otherwise.

Boston Partners Global Investors, Inc. (Boston Partners) is an Investment Adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training. Boston Partners is an indirect, wholly owned subsidiary of ORIX Corporation of Japan. Boston Partners updated its firm description as of November 2018 to reflect changes in its divisional structure. Boston Partners is comprised of two divisions, Boston Partners and Weiss, Peck & Greer Partners.

Securities offered through Boston Partners Securities, LLC, an affiliate of Boston Partners.